The Lapiang Malaya movement formed in the 1940s and was part political, part religious organization. In May 1967 their leader called on then-President Ferdinand E. Marcos to resign so a government formed of their movement could take over. More than 500 members gathered at their headquarters along Taft Avenue in Pasay City in what began as a peaceful demonstration. The Philippine Constabularly repeatedly attempted to break up the assembly which eventually boiled over into violence on both sides – with 32 members of Lapiang Malaya killed and over 300 more arrested and taken to Camp Crame. In the aftermath, the Philippine Constabularly came out with alleged reports that the group was linked to communists to justify their actions.5

In the 1960s the Philippines experienced increasing poverty; the government was falling deeper into debt and questions regarding the US’ involvement in our economy and presence of Military bases were raised. With the nation in crisis as inflation spiraled out of control and the steady devaluation of the peso and rampant unemployment, a series of protests broke out mostly centering around student movements but also involving workers groups and peasant organizations. In the late 1960s several key demonstrations took place, and most were harassed by police or even violently dispersed. In 1967 calls for a constitutional convention to revise the 1935 Constitution began surfacing as a response to the growing discontent brought about the stark inequalities in society.6

It’s against this backdrop that President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. wins his first reelection in November 1969. Just two months later in January 1970 a rally outside of Marcos Sr.’s SONA calling for a non-partisan Constitutional Convention turns violent. Several student movements were in attendance as well as labor groups and peasant organizations; they were met by a strong security force. While the protest began peacefully, it eventually devolved into violence with the uniformed personnel using what some considered excessive force to disperse protesters. A Senator present called for the security forces to cease their attacks but was told that only the MPD chief of police could give the order. From there several more public protests and rallies continued throughout the first quarter of 1970 in what is now called the First Quarter Storm.7 8 9

During this period several protests broke out only to be violently dispersed by police. While students were a driving force for the protests; they were often joined by workers, peasants, urban poor, drivers and members of other sectors. With each violent dispersal, more people were inspired to take to the streets to protest police brutality and repression. During one dispersal a student was captured by police and tortured to death. The unrest dissipated towards the end of March 1970, but this period is considered a watershed moment in the opposition against Marcos Sr. 10 11 12

Just a year later, students joined jeepney drivers in striking against rising oil prices. Barricades went up in UP Diliman, UP Los Banos and along the University Belt. In UP Diliman, what was initially a peaceful protest broke out in violence when a professor tried to forcibly disperse students. His car was then damaged by students throwing pillboxes and he responded by opening fire on the students, killing one and injuring at least one more. Following his arrest, Metrocom entered the campus, scattering students with hundreds running to the College of Arts and Sciences Building and barricading themselves in there. Several students were arrested. And from that point on the fight was no longer about oil price hikes but about the military incursion on campus grounds. This was the first day of what came to be called the Diliman Commune. Over the next few days students skirmished with police and military forces. Students took over the UP Press and DZUP radio station. The barricades were eventually taken down voluntarily in exchange for several demands, including a gasoline price rollback and justice for the student killed on the first day. However, it would appear none of the demands were ever met.13 14

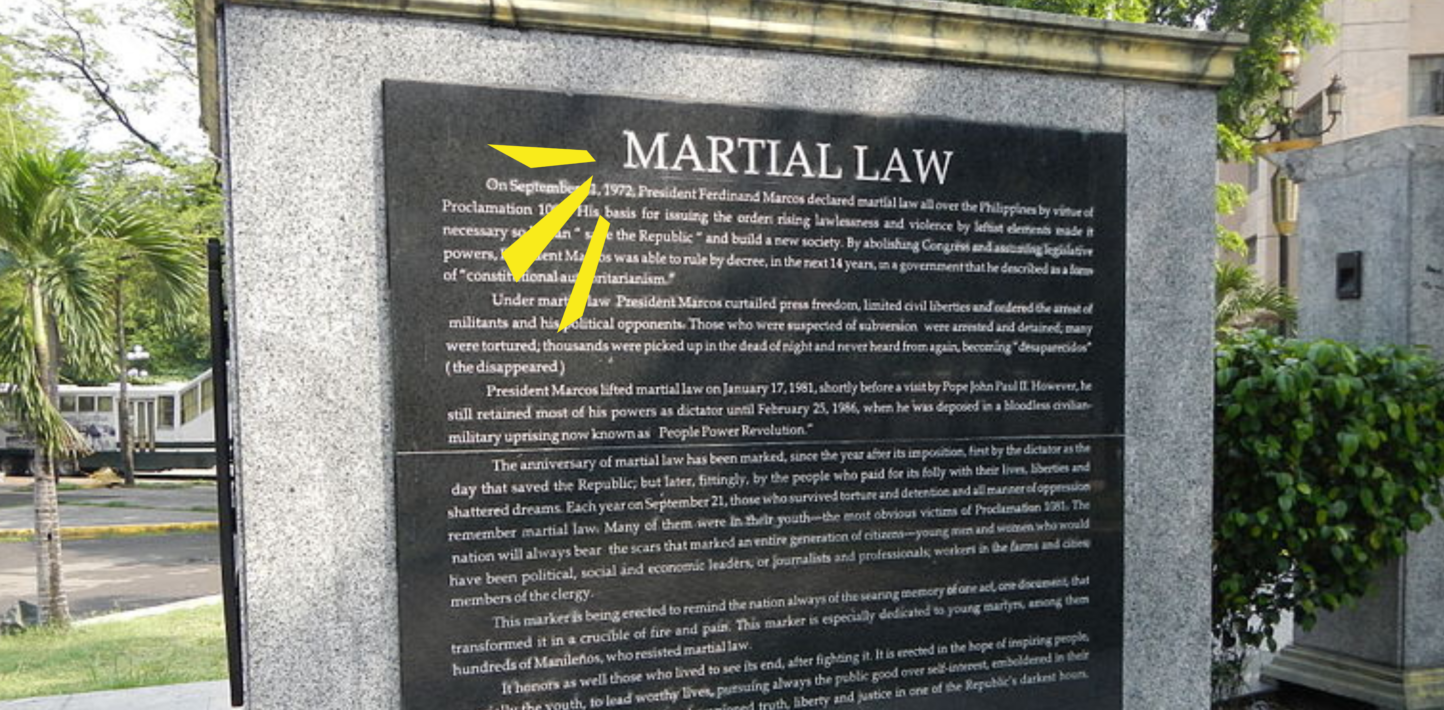

In August of that same year the Plaza Miranda Bombing happened, killing nine people and wounding more than 100. While it continues to be uncertain who perpetrated this attack, it is cited by President Marcos Sr. in his Proclamation 889 suspending the Writ of Habeas Corpus. Following the Writ’s suspension, several prominent activists were arrested, and security forces cracked down on mass organizations. This prompted the formation of Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties. The alliance brought together a broad group of activists, uniting them with three basic demands: lift the writ of habeas corpus; release political prisoners; and resist any plan by the Marcos government to declare martial law. They held a series of rallies, the largest being on September 21st 1972 just hours before President Marcos Sr. declared Martial Law.15

With the proclamation of Martial Law, the crackdown on activism intensified. However, that did not stifle the spirit of Filipinos. Protests continued even during the repressive years of Martial Law. One of the longest and most sustained was the struggle against the Chico River Basin Development Project by the Kalinga Indigenous communities from the early 1970s to 1980. The project involved the construction of four massive dams – two in the Mountain Province and two in Kalinga. If the dams were constructed it would have wiped away Indigenous communities in eight towns, impacting around 300,000 people. When peaceful negotiations broke down, Indigenous groups turned to civil disobedience – blockading roads with boulders and pitching construction equipment into the river. Indigenous women played a key role – tearing down workers dormitories with their bare hands and driving away survey teams. 16

The Marcos government responded with violence and bloodshed. The military were sent in and the area was declared a “free-fire zone” where any “trespassers” could be shot indiscriminately. In April 1980, the assassination of a key figure in the struggle, a village elder named Macli-ing Dulag, by members of the armed forces sparked wider mobilization across sectors in the region. The project was eventually abandoned in 1986 and has become a landmark case in the way the government and even international bodies such as the World Bank handle projects involving Indigenous people and their Ancestral Lands. 17

In August 1983 key opposition leader Ninoy Aquino was assassinated on the tarmac of Manila International Airport. His death sparked protests starting from his funeral procession which lasted for more than ten hours and was attended by over a million people until the following year. On the anniversary of his death in 1984 rallies were held all over the country with an estimated 450,000 at the Rizal Park alone. The rallying cry for the protesters was the resignation of President Marcos Sr. 18 19

Another set of protests against the Marcos Sr. Administration were those against the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) which started almost as soon as he annouced the decision to construct the plant in 1973 but really became organized in January 1981 with the organization of the Nuclear Free Philippines Coalition. This alliance came together originally to oppose the construction and operation of the BNPP but eventually expanded its campaign goals to include the closing of US miltary bases as well. There were several rallies in 1983 and 1984; however, in June 1985 there was the “Welgang Bayan Laban sa Plantang Nukleyar” (People’s Strike) in Balanga, the capital of Bataan. This was a three-day strike which on the third day forced the entire province of Bataan to a standstill with the rest of the nation almost following close behind. 33,000 activists and Filipino citizens mobilized by 22 anti-nuclear organizations participated in the largest protest action of the campaign. The BNPP never opened under the Marcos Sr. Administration and thanks to public pressure and the tense political climate the Aquino administration which followed postponed its use in April 1986. 20

Throughout history, protest has been a powerful tool for change. But governments around the world are cracking down on protests and it must be protected.

Protect the protest

Add your voice to our global call to protect the protest and join our campaign today.